The Mystery of the Chinese Junk

Posted by Dylan Beattie on 25 October 2016 • permalinkYou know it’s going to be one of those days when, just as you’re about to put on your headphones and get into ‘the zone’, you overhear somebody saying the fateful words ‘ok, then maybe we’ll need to get Dylan to look at it.’

See, amongst the many hats I wear in the course of a given week, there’s one that’s probably labelled ‘dungeon master’ I’m the one who remembers where all the bodies are buried, because – for all sorts of reasons that made very good sense at the time – I probably helped bury most of them. And on this particular day, the source of so much excitement was our venerable Microsoft Dynamics CRM v4 server. It started out with a sort of general grumbling on the support channel about CRM4 being slow… but by the time it was handed over to me to look into, it was beautifully summarised as ‘dude… there’s Chinese in the Windows event log’

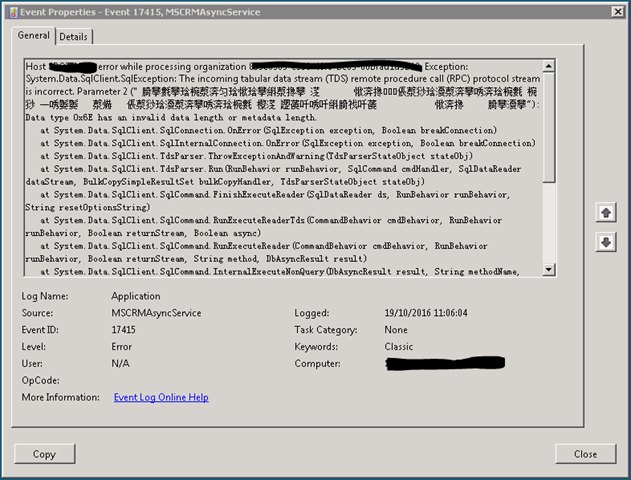

And, sure enough, there is – complete with the lovely Courier typeface that Windows Event Viewer kicks into when you get errors so weird that good old Microsoft Sans Serif can’t even display them:

Now, whilst it’s been a while since I’ve done any serious work on our old CRM system, I’m pretty sure it’s not supposed to do that – so we start investigating. Working theory #1: some sort of vulnerability has resulted in attackers injecting Chinese characters into our database – whilst CRM4 is generally pretty well insulated from any public-facing code, there’s one or two places where signup forms would generate CRM Leads, that sort of thing. So we start grepping the entire database for one of the Chinese strings we’ve found in the event log.

Whilst this is going on – and trust me, it takes a while – I decide to share my excitement via the wonder of social media. This turns out to be a Really Good idea, because... well, here's what happened...

"The incoming tabular data stream TDS RPC protocol stream is incorrect. Parameter ("䐀攀氀攀琀椀漀渀匀琀愀琀攀..." Oh. It's gonna be one of THOSE days.

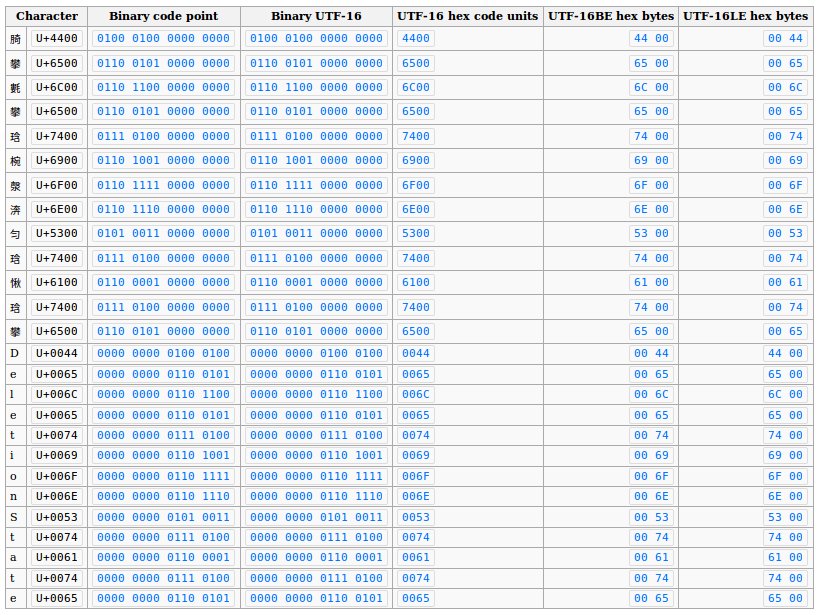

— Dylan Beattie (@dylanbeattie) October 18, 2016@dwm @dylanbeattie The low bits are all null, so this probably UTF-16LE being mistaken for UTF-16BE (or vice versa...?). pic.twitter.com/D0IO4px9YE

— Fake Unicode ⁰ (@FakeUnicode) October 18, 2016You see in @FakeUnicode's screenshot there, the words ‘DeletionState’ appear quite clearly at the bottom of the message?

Whilst this is going on, our database search comes back reporting that there’s no mysterious Chinese characters in any of our CRM database tables. Which is good, since it means we probably haven’t been compromised. So, next step is to work through that Unicode lead, see if that gets us anywhere. Because .NET has a built-in encoding for big-endian Unicode, this is pretty simple:

var source = "䐀攀氀攀琀椀漀渀匀琀愀琀攀";

var bytes = Encoding.BigEndianUnicode.GetBytes(source);

var result = Encoding.Unicode.GetString(bytes);

Console.WriteLine(result);

Turns out – just as in FakeUnicode’s screenshot – that’s the text “DeletionState” with the byte order flipped. We grabbed a few examples of the ‘Chinese’ text from the event log, ran it through this – sure enough, in every single case it’s a valid CRM database query that’s somehow been flipped into wrong-endian Unicode. At this point we start suspecting some sort of latent bug – this is old software, running on an old operating system,talking to an old database server, and sure enough, a bit of googling turns up a couple of likely-looking issues, most of which are addressed in various updates to SQL Server 2008. We take a VM snapshot in case everything goes horribly wrong, and one of the Ops gang volunteers to work late to get the server patched.

Next morning, turns out the server hasn’t been patched – because every single download of the relevant service pack has been corrupted. At which point all bets are off, because chances are the problem is actually network-related – which also explains where the ‘Chinese’ is coming from.

OK, let’s capture a stream of bytes from somewhere. Like, say, from the TDS data stream used by the MSCRMAsyncService

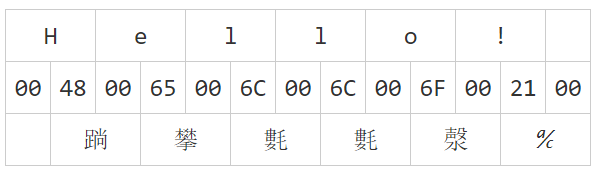

What does that say? If you think you know the answer, you’re wrong. Pop off and read The Absolute Minimum Every Software Developer Absolutely, Positively Must Know About Unicode and Character Sets (No Excuses!) – done? Awesome. NOW what do you think it says?

See, we have no idea. It’s a stream of bytes. Without some indication of how we’re supposed to interpret those bytes, it’s meaningless. OK, I’ll give you a clue – it’s UTF-16. Now can you tell what it says? No, you can’t – because (1) you don’t know whether it’s big-endian or little-endian, and (2) you don’t know where it started.

If we assume it’s big-endian, then the first byte pair – 00 48 – would encode the character ‘H’, the second byte pair – 00 65 – would encode ‘e’, and so on. If we assume it’s little-endian, then the first byte pair – 00 48 – encodes the character 䠀 – and suddenly the mysterious Chinese characters in the event log start to make sense.

Of course, the data stream between the MSCRMAsyncService and the SQL server hasn’t actually flipped from little-endian UTF-16 to big-endian – what’s happened is that the network connection between them is dropping bytes. And if you drop a single byte – or any odd number of bytes – from a little-endian Unicode stream, you get a sort of off-by-one error right along the rest of the data stream, resulting in all sorts of weirdness – including Chinese in the event logs.

Turns out there was a problem with the virtual network interface on the SQL Server box – which was causing poor performance, timeouts, bizarre query syntax errors, Chinese in the event logs, and corrupted service pack downloads. Fortunately the databases themselves were intact, so we offlined them, cloned the virtual disk they were sitting on, attached that to a different server and brought them back online.

Every once in a while, you get a weird problem like this. I’ve seen maybe half-a-dozen problems in my entire career that made absolutely no sense until they turned out to be a faulty network connection, at which point generally you not only solve the problem, but explain a whole load of other weirdness that you hadn’t got round to investigating yet. The only thing more fun than dodgy networks is dodgy memory – but that’s a post for another day.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about the title of this post, you clearly haven’t studied the classics.