Confession Time. I Implemented the EU Cookie Banner

Posted by Dylan Beattie on 07 January 2016 • permalinkTroy Hunt kicked off 2016 with a great post about poor user experiences online – a catalogue of common UX antipatterns that “make online life much more painful than it needs to be”.

One of the things he picks up on is EU Cookie Warnings – “this is just plain stupid.” And yeah, it is. Absolutely everybody I know who added an EU cookie warning to their website agrees – this is just plain stupid. But for folks outside the European Union, it might be insightful to learn just why these things started appearing all over the place.

First, a VERY brief primer on how the European Union works. There’s currently 28 countries in the EU. The United Kingdom, where I live and work, is one of them. One of the aims of the EU is to create a consistent legal framework that covers all citizens of all its member states. Overseeing all this is the European Parliament. They make laws. It’s then up to the governments of the individual member states to interpret and enforce those laws within their own countries.

So, in 2009, the European Parliament issued a directive called 2009/136/EC – OpenRightsGroup has some good coverage of this. The kicker here is Article 5(3), which says

“The storing of information or the gaining of access to information already stored in the user’s equipment is only allowed on the condition that the subscriber or user concerned has given their consent, having been provided with clear and comprehensive information in accordance with Directive 95/46/EC, inter alia, about the purposes of the processing. This shall not prevent any technical storage or access for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network, or as strictly necessary in order for the provider of an information society service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user to provide the service.”

In a nutshell, this means you can’t store anything (such as a cookie) on a user’s device, unless

- You’ve told them what you’re doing and they’ve given their explicit consent, OR

- It’s absolutely necessary to provide the service they’ve asked for.

Directive 2009/136 goes on to state (my emphasis):

“Under the added Article 15a, Member States are obliged to laydown rules on penalties, including criminal sanctions where applicable to infringements of the national provisions, which have been adopted to implement this Directive. The Member States shall also take “all measures necessary” to ensure that these are implemented. The new article further states that “the penalties provided for must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive and may be applied to cover the period of any breach, even where the breach has subsequently been rectified”.

Golly! Criminal sanctions? Retrospectively applied, even for something that we already fixed? That sounds pretty ominous.

Anyway. Here’s what happens next. Directive 2009/136 means that is is now THE LAW that you don’t store cookies without consent, and the various member states swing into action and try to work out what this means and how to enforce it. In the UK, Parliament interpreted this via something called the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) (Amendment) Regulations 2011, which would come into effect in 2012.

Anyway. Here’s what happens next. Directive 2009/136 means that is is now THE LAW that you don’t store cookies without consent, and the various member states swing into action and try to work out what this means and how to enforce it. In the UK, Parliament interpreted this via something called the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) (Amendment) Regulations 2011, which would come into effect in 2012.

My team and I found out in late 2011 that, when the new regulations came into force on 26 May 2012, we would be breaking the law if we put cookies on our user’s machines without their explicit consent. And nobody had the faintest idea what that actually meant, because nobody had ever broken this law yet, so nobody knew what the penalties for non-compliance would be. The arm of the UK government that deals with this kind of thing is the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), who have a reputation for taking data protection very seriously, and the power to exact fines up to £500,000 for non-compliance. The ICO also usually publish quite clear and reasonable guidelines on how to comply with various elements of the law – but that takes time, so in late 2011 we found ourselves with a tangle of bureacracy, a hard deadline, the possibility of severe penalties, and absolutely no guidance to work from.

So… we implemented it. Despite it being a pointless, stupid, ridiculous endeavour that would waste our time and piss off our users, we did it - because we didn’t want to end up in court and nobody could assure us that we wouldn’t.

We built a nice self-contained JavaScript library to handle displaying the banner across our various sites and pages.

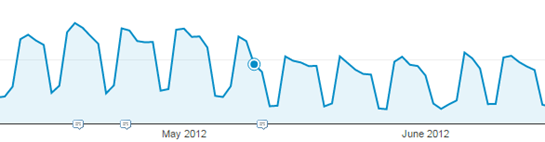

Instead of just plastering something on every page saying “We use cookies. Deal with it”, the approach taken by most sites - we actually split our cookies into the essential ones required to make our site work, and the non-essential ones used by Boomerang, Google Analytics and other stats and analytics tools. And we allowed users to opt-out of the non-essential ones. We went live with this on 10th May 2012. Around 30% of our users chose to opt-out of non-essential cookies – meaning they became invisible to Google Analytics and our other tracking software. Here’s our web traffic graph for April – June 2012 – see how the peaks after May 10th are suddenly a lot lower?

On 25th May 2012, ONE DAY before the new regulations became law, the ICO issued some new guidance, which significantly relaxed the requirements around ‘consent’. “Implied consent” was suddenly OK – i.e. if your users hadn’t disabled cookies in their browser, you could interpret that as meaning they had consented to receive cookies from your site.

They also announced that any enforcement would be in response to user complaints about a specific site:

“The end of the safe period "doesn't mean the ICO is going to launch a torrent of enforcement action" said the deputy commissioner and it would take serious breaches of data protection that caused "significant distress" to attract the maximum £0.5m non-compliance fine.” (via The Register)

So there you have it. Go to http://www.spotlight.com/ and, just once, you’ll see a nice friendly banner asking if you mind us tracking your session using cookies. And if you opt out, that’s absolutely fine – our site still works and you won’t show up in any of our analytics. Couple of weeks of effort, a nice, clean, technically sound implementation… did it make the slightest bit of difference? Nah. Except now we multiply all our Analytics numbers by 1.5. And yes, we periodically review the latest guidance to see whether the EU has finally admitted the whole thing was a bit silly and maybe isn’t actually helping, but so far nada – and in the absence of any hard evidence to the contrary, it’s hard to make a business case for doing work that would make us technically non-compliant, even if the odds of any enforcement action are minimal.

Now, if the European Parliament really wanted to make the internet a better place, how about they read Troy’s post and ban popover adverts, unnecessary pagination, linkbait headlines and restrictions on passwords? Now that’s the kind of legislation I could really get behind.